Despite a 2023 Supreme Court decision banning race-conscious admissions at U.S. colleges and universities, the racial makeup of the University’s Class of 2028 is similar to the year before, according to data obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request by The Cavalier Daily. Other demographic splits — including gender, in-state and out-of-state status and first-generation status — also remained relatively consistent with demographic data from the Class of 2027.

The data referenced in this article adheres to federal reporting guidelines, which categorize international students and non-residents of the United States as “Global” instead of classifying them into a racial category. These guidelines also contain a separate category for students self-identifying with two or more races.

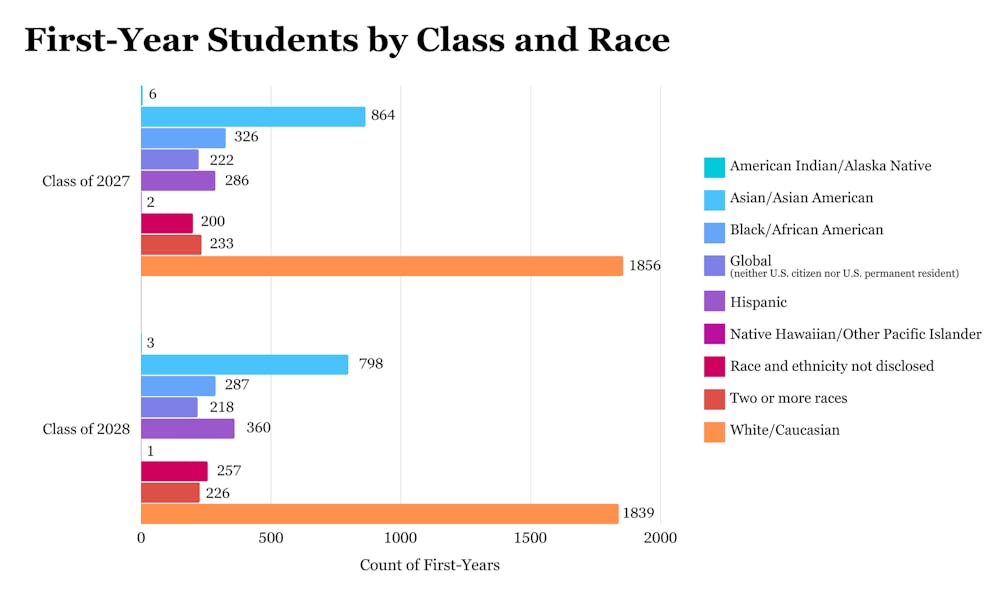

The greatest racial demographic shift for this first-year class was among Hispanic students, increasing from 7.2 percent of the Class of 2027 to 9 percent of the Class of 2028. However the number of Asian and Black students decreased slightly — Asian students represented 21.6 percent of the first-year class last year compared to 20 percent this year, and Black students represented 8.2 percent last year compared to 7.2 percent this year.

Beyond racial demographics, the Class of 2028 is 56.6 percent female and 43.4 percent male, as compared to 57.2 percent female and 42.8 percent male the year prior. The number of out-of-state students dropped from 34.4 last year to 32.3 percent this year, while the number of Virginians rose from 65.6 percent to 67.7 percent. Additionally, the number of first-generation college students rose from 17.5 percent last year to 18.8 percent this year.

The Class of 2028 was the first to apply to the University following a Supreme Court ruling on two cases last June — Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina and Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard University — that found affirmative action policies at Harvard and UNC unconstitutional, effectively banning race-conscious admissions practices at colleges and universities nationwide.

Following the decision, the Virginia legislature subsequently voted Jan. 2024 to end consideration of legacy status — defined as having a family relation to an alumnus of a college or university — in the admissions processes of the Commonwealth’s state schools. Children of University graduates make up 12.9 percent of the Class of 2028, a decrease from 14.7 percent in the Class of 2027.

With the Supreme Court’s decision impacting the racial diversity of colleges and universities differently, Law Prof. Kim Forde-Mazrui said that it is difficult to identify the specific reasons why the racial makeup of the University’s newest class looks similar to that of the previous year, but that there are several possible explanations.

According to Forde-Mazrui, one potential explanation is that while colleges and universities cannot specifically ask for a student’s racial or ethnic affiliation as indicated in any type of checkbox, admissions officers can still consider how an applicant’s race has affected their lived experiences, which may help their application depending on the institution’s diversity goals.

“A lot of these so-called soft factors — personal essays, letters of recommendation — had already been part of the process,” Forde-Mazrui said. “So maybe the change isn’t that significant, given that they can still consider racial experience.”

According to Deputy University Spokesperson Bethanie Glover, while the University adhered to both Supreme Court and state guidelines — restricting application reviewers’ access to information about applicants’ race and legacy status — it also added one of these open-ended prompts to its application. The prompt, first added for the Class of 2028, asks applicants to share their personal experiences and how they would contribute to the University community if admitted.

Forde-Mazrui also said that the Supreme Court has not forbidden considering other race-neutral factors that can contribute to a diverse class, such as the number of students who are first-generation or who come from high schools with historically low college application rates. According to Forde-Mazrui, students from these populations have historically been more racially diverse than the overall applicant pool, so universities could give preference to these applicants with the intent of achieving racial diversity.

Forde-Mazrui cited Texas’ “Top 10 Percent Law,” a 1997 bill passed in the wake of a circuit court decision banning affirmative action policies in the state, as an example of this approach. The bill guaranteed the top 10 percent of high school students entry to state-funded universities, and while the bill did not technically favor any particular demographic, Forde-Mazrui said it was explicitly designed to boost admission among Black and Hispanic students.

Forde-Mazrui offered another potential explanation for the Class of 2028’s relatively unchanged racial makeup — he said that some schools have invested in outreach programs to help students from traditionally underrepresented high schools apply to higher education, citing these programs as one long-term approach colleges might pursue when looking to ensure diversity in their classes.

At the University, Glover said outreach programs into low-income areas with historically low numbers of applications to the University helped ensure the class’s socioeconomic diversity.

“The socioeconomically and culturally diverse profile of this year's class can be largely attributed to the hard work of many partners … who ensured that we were reaching every corner of Virginia to invite applications from talented students from all backgrounds,” Glover said.

In particular, Glover said that programs such as the Virginia College Advising Corps — a division of the Provost’s Office with the stated mission of boosting the number of first-generation, low-income and underrepresented students in higher education — supported many students in the incoming class by providing them with college advising services.

According to VCAC Director Alex Johnston, while the organization’s day-to-day operations have remained unchanged in the wake of the Supreme Court’s affirmative action ruling, their mission has become increasingly important because they want to encourage students in what may feel like a discouraging circumstance. She said that providing students with college advisors remains central to VCAC’s work.

“College advisors are really uniquely positioned in schools [as staff members with] the capacity to think solely about post-secondary planning for students,” Johnston said. “[Advisors] help them find their voice and share their unique stories as they are going through the admissions and financial aid application processes.”

According to Glover, 271 students, or 6.8 percent, of first-year students in the Class of 2028 who have not received any prior postsecondary education received VCAC assistance during the college application process. She said this percentage was an increase from the previous two years, with VCAC-supported students making up 5.3 percent and 4.2 percent of the Class of 2027 and Class of 2026, respectively.

In addition to working closely with partners such as VCAC, Glover said that the University improved its Days on the Lawn program — an annual program allowing admitted students to visit Grounds — to offer travel vouchers and fee waivers to low-income families in order to help them determine whether the University is the right fit for their college goals.

“We’re glad to be able to offer these programs and accommodations to support students from all walks of life in the important decision on where to attend college,” Glover said.