The University is working to establish itself as a national leader in data science during a time when the field itself is expanding rapidly. Most notably, the new School of Data Science was founded in 2019, with its dedicated building opening earlier this year. This University’s focus on data extends beyond the new school — it has also recently invested substantially in developing its Northern Virginia campus, which offers programs noticeably concentrated in data science or related fields like AI and Information Technology, a deliberate choice, as Northern Virginia is often considered the global hub of data centers. These University projects provide a good example of forward-looking efforts to keep up with global trends. However, in doing so, the University turns a blind eye to the drawbacks of data science — data science as it stands today is simply not sustainable in the long run.

Technological developments and the University’s geographic location make the decision to focus on data science a logical one. Artificial intelligence has exploded in recent years, and since AI functions by analyzing vast quantities of data, the expansion of data processing and that of AI go hand in hand. The sheer quantity of data itself has already grown enormously, with 90 percent of the world’s data being created in the last two years. These effects are felt especially in Virginia, which dominates the data processing industry — Virginia is the world’s largest data center market, providing services for numerous global corporations including Microsoft, Amazon and Meta. This provides an additional incentive for the University to push to establish itself in this field, in the same way a Silicon Valley university would be motivated to focus on technology.

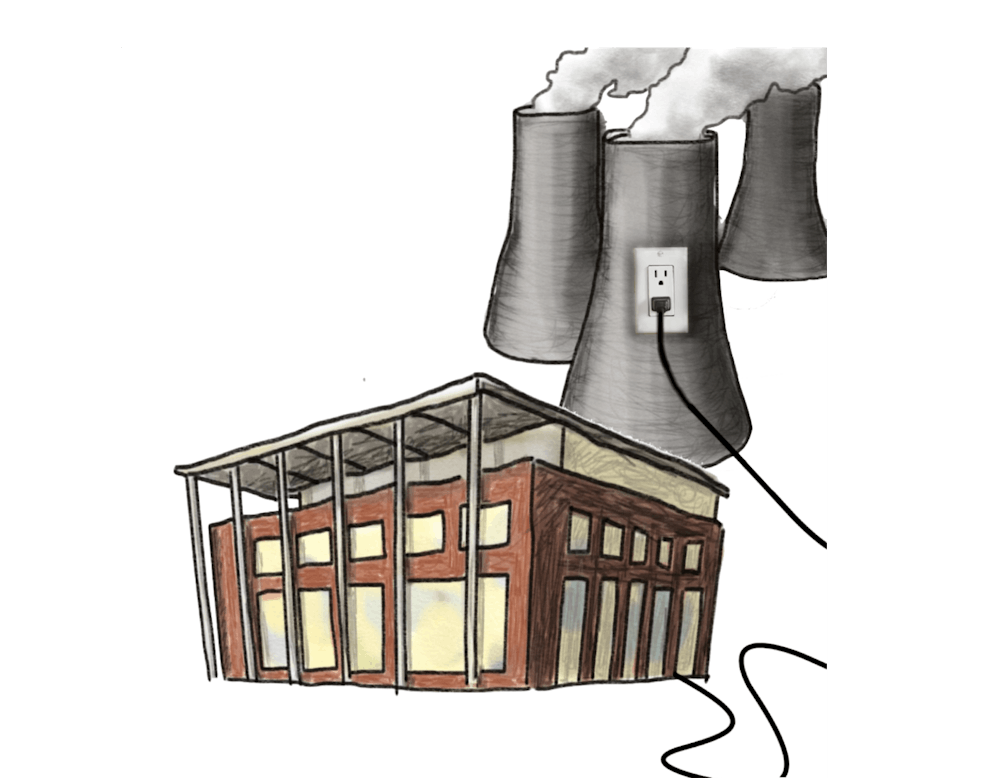

However, as the University rides the data science wave, it ignores how this industry has grown into a global environmental threat. U.S. energy consumption is expected to increase by 2.4 percent by 2030, with data centers accounting for more than a third of that growth. This may seem small, but it is a massive change considering energy consumption has been constant for the past decade. Natural gas still sources around 50 percent of energy consumed in Virginia, meaning growing energy consumption will inevitably increase the use of natural gas and the harmful emissions it produces. Put simply, Virginia does not have sufficient clean energy sources to support the expansion of data science without there also being a substantial corresponding increase in greenhouse gas emissions — these emissions being the overwhelming culprit of climate change.

While the University is not responsible for the state’s failure to supply its data processing obsession in a sustainable manner, the University’s obvious efforts to associate itself with this industry make it also obligated to acknowledge and consider these negative consequences. Sure, the University does have a duty to provide students with expertise in professionally relevant fields, data science included — but it also has a duty to consider the moral implications of the fields for which it prepares its students. Of course those who study, research or teach data science are not deserving of blame, but its deep connection with climate change, perhaps the defining issue of today, means data science as it stands is nonetheless not the slam dunk the University’s wholehearted embrace of it might suggest.

Thankfully, the University can take a number of steps to counteract these negative effects without abandoning its commitment to the data science industry. First, the University should promote energy innovation by opening more avenues for raising the funds necessary to conduct research in the field of sustainable energy. In recent years, the University has matched its funding of research initiatives related to data science with fairly equivalent funding for those related to sustainability. However, its data science programs are now far more heavily supported thanks to the $120 million gift to the School of Data Science, while financial backing for sustainability work appears unchanged.

Directing more of the University’s budget for research funding toward green energy projects would allow for the expansion of genuinely impactful research already taking place in projects like the Fontaine Central Energy Plant. This shift in funding would not be detrimental to other fields, including data science, which currently seem to be more attractive to private donors. The University should also leverage its flagship status to collaborate with the Virginia government — which is ostensibly receptive to innovative energy plans — on these research efforts.

As an additional, broader solution, the University should shore up its efforts toward sustainability in its own operations. Its 2030 Sustainability Plan sets fairly admirable goals including reaching carbon neutrality by 2030. While real progress has been made — the University has reduced carbon emissions by 44.8 percent since 2010 — a quick look at the data uncovers that it is highly unlikely that this goal will be met. Emissions have actually increased since 2020, and it would take a dramatic shift to even approach zero emissions in the next six years. Managing to actually uphold its commitments is a second fundamental step for the University to center sustainability amidst its continued data science expansion.

The University — along with much of the world — appears committed to the idea of a future defined by data, but this expectation lacks the necessary dedication to meeting this future’s energy needs in a sustainable way. The University’s commitment to the field of data science positions it well for tomorrow, but the potential benefits of this effort will fall flat if the University does not make a coinciding commitment toward the sustainability of its data science endeavors.

Nathaniel Carter is a viewpoint writer who writes about health, technology and environment for The Cavalier Daily. He can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions represented in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.