Student engagement at the University and across the nation has increased, specifically in the form of student-led activism and the presence of increasingly numerous student groups. This, in turn, has created a new generation of movers for change who should be celebrated for their deep engagement with the spaces they inhabit. However, while this increased engagement is laudable, it is not implicitly sustainable. Student-led groups and activism have long confronted a huge barrier when thinking long-term — their group’s institutional memory will never exceed four years which in turn reduces their ability to acquire, cultivate and maintain institutional knowledge about the University.

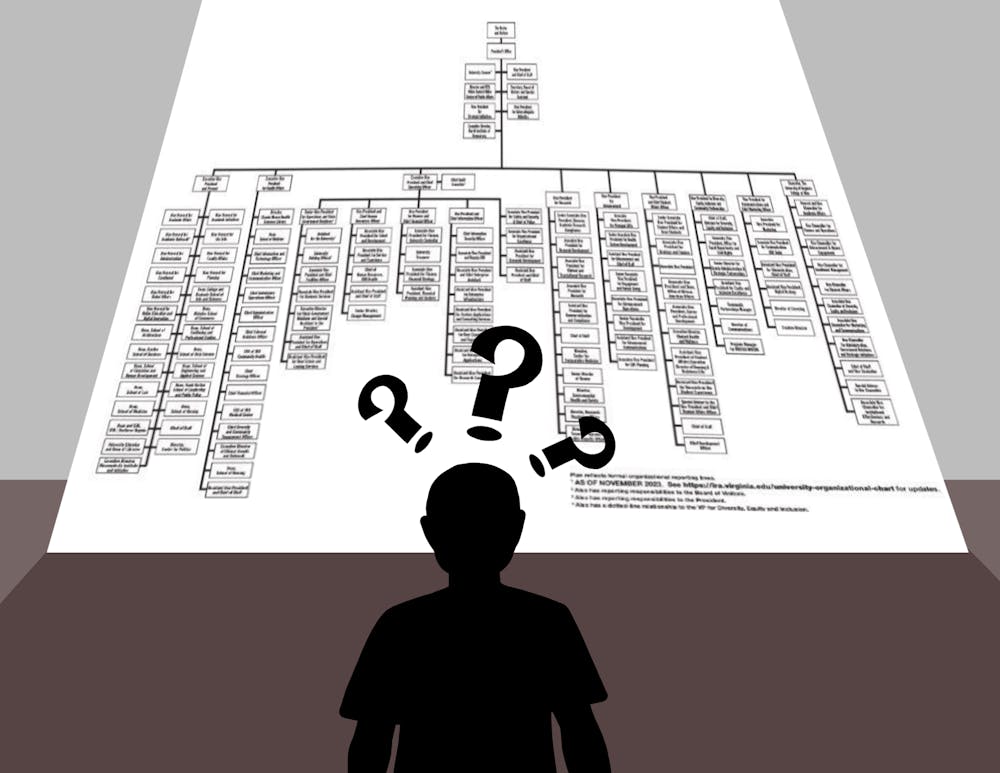

Institutional knowledge about the University, in this article, refers to the understanding a student organization has of the University, specifically the insights regarding the tangible structure and unwritten cultural nuances. The University has an extremely complicated and ever-changing hierarchy of offices, departments and administrative positions that are created with the intention of facilitating student engagement and providing resources to groups and individuals. Often, student groups not only seek out these resources to advance their own causes, but will also work to connect their members with them. Unfortunately, however, this complex structure, which offers resources spanning from student affairs to health services, is difficult to navigate and use to its fullest extent.

Currently, the University does little to equip student groups with institutional knowledge. Rather, groups are expected to navigate around and interact with this extremely complex system on their own, something which fails to ensure that they are both cognizant of and able to use the resources available to them. This is, in many ways, at odds with an institution that aims to place student self-governance at the heart of its mission.The University claims to be a space which empowers student groups to be active participants in the hopes of inculcating future global leadership. However, this rhetorical empowerment means very little if it is not backed up by tangible support and transparent structures. Without the establishment of a framework to educate such students, this important yet complex knowledge is difficult to pass down and maintain.

Maintaining this institutional knowledge as permanent and clear rather than transitory and opaque is essential to promoting productive discourses between student groups and administrators. Recently, student groups, in endeavoring to change institutional policies, have critiqued the lack of visibility of University structures, which they contend makes it difficult to engage in good faith dialogue with administrators. Consider the University Investment Management Company which is a common target of criticism of student divestment initiatives across Grounds. Student groups like DivestUVA have worked to pressure the University to withdraw its investments in fossil fuel and weapons manufacturing companies.

However, their efforts have been complicated by the complete lack of transparency with which UVIMCO operates, a lack behind which the University can hide when dismissing student group concerns. Through this example, it becomes clear that institutional knowledge is not only necessary for student groups’ ability to access resources but also for their ability to engage in good faith conversations with administrators — these are only possible with a deep cognizance of the intricacies of the structures of this institution.

The University must take steps to provide its students with the means to easily navigate the resources, offices and structures of the institution. Commitments to facilitating this knowledge may take the form of modules students are required to complete before enrolling at the University. Or it might mean more comprehensive flow charts about the hierarchy of the University and clearly delineated definitions as to what each office does. Student groups across Grounds can neither accurately criticize nor adequately commend this institution unless they understand its layout and functions.

While much of this information would be targeted at student groups, it would inevitably trickle down to the individual, better disseminating information about programs and resources. In this way, implementing institutional knowledge also works to serve individual students, specifically of underrepresented backgrounds, through equipping them with information that is not readily available nor passed down to them. Given a complex organizational structure, first-generation and students of immigrant parents who do not have a legacy in American higher education, are posed with further disadvantages when the University fails to educate its student body on the functions of the system that serves them.

When the University does not assume the responsibility of educating its students on the structures of its institution, it does not equip its students or its student groups with the knowledge and resources to succeed to their fullest extent. Understanding one’s institution is critical in developing future leaders and models of change. In this way, institutional knowledge is not merely a resource but a vital foundation for meaningful leadership and activism, essential for fostering student self-governance and equipping students to drive change. Elucidating institutional knowledge to students is an imperative that the University must fully embrace to fulfill its mission of developing tomorrow’s leaders.

Farah Eljazzar is an opinion columnist who writes about identity and culture for The Cavalier Daily. She can be reached at opinion@cavalierdaily.com.

The opinions expressed in this column are not necessarily those of The Cavalier Daily. Columns represent the views of the authors alone.