Take a look around you. Due to the school-wide Batten Curve, your grade in a class within the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy will not just be determined by your hard work, but also by the performances of your classmates. The Batten Curve states that each Batten class should have a mean GPA around 3.5. This pedagogical tool, intended to support consistency across the school’s classes, has stirred student concerns about unfair grade distributions, deflated GPAs and unnecessarily limited postgraduate opportunities for Batten students. Beyond those very tangible concerns, the Batten Curve cultivates a toxic culture of competitiveness that undermines professors’ autonomy and jeopardizes classroom dynamics.

To be clear — not all curves are harmful in the way that the Batten Curve is. Indeed, professors may sparingly use a curve to compensate for a poorly written exam, and at some point, we all have probably benefited from a curve. However, Batten takes this practice one step too far with its top-down imposition. Under this policy, Batten asks that all professors — in every single class within the school — adjust their students' grades in a normative distribution around a 3.5 GPA. Simply put, this curve is a problematic demand that intrudes into professors’ classrooms and destabilizes students' academic lives.

Yet, Batten has chosen and continues to choose this path. In doing so, it is the only school at the University that imposes a curve policy from the top down. Unsurprisingly, this unwavering implementation of the curve sacrifices Batten professors’ freedom to lead and adapt their own classrooms — a grave pedagogical mistake. Beyond the years of expertise that professors bring, they intrinsically have a ground-level knowledge of their unique classroom dynamics each year. And these dynamics do vary — one year, a class may be filled with dynamos, and the next, it could be filled with exhausted fourth-years. But the Batten Curve suggests that classroom dynamics from year to year and semester to semester are standard and predictable. They are not.

Given this variety, professors are the ones best equipped to develop their own grading policy, as they do in every other school at the University. But, in Batten, if a professor wants this degree of flexibility, they must first submit a justification to Batten. It is hard to imagine that this extent of micromanagement and top-down oversight is warranted. After all, at the end of the day, it is in students’ best interest that professors are empowered to adapt their grading policies to their specific classrooms. Forcing professors to abide by a standardized grading policy at the beginning of the semester therefore diminishes the freedom of professors to analyze student performance on their own terms and adjust grading decisions accordingly.

Batten professors are further obliged to this standard Batten curve in the name of maintaining academic rigor in the school. Academic rigor, or the standards of excellence that professors expect from their students, is perceived to be undermined when too many students receive high GPAs. In response to this perception, Batten argues that the curve is necessary because a wide range of GPAs displays the school’s degree as more rigorous and valuable. It is no longer enough for a Batten student to work hard and feel challenged by the course material.

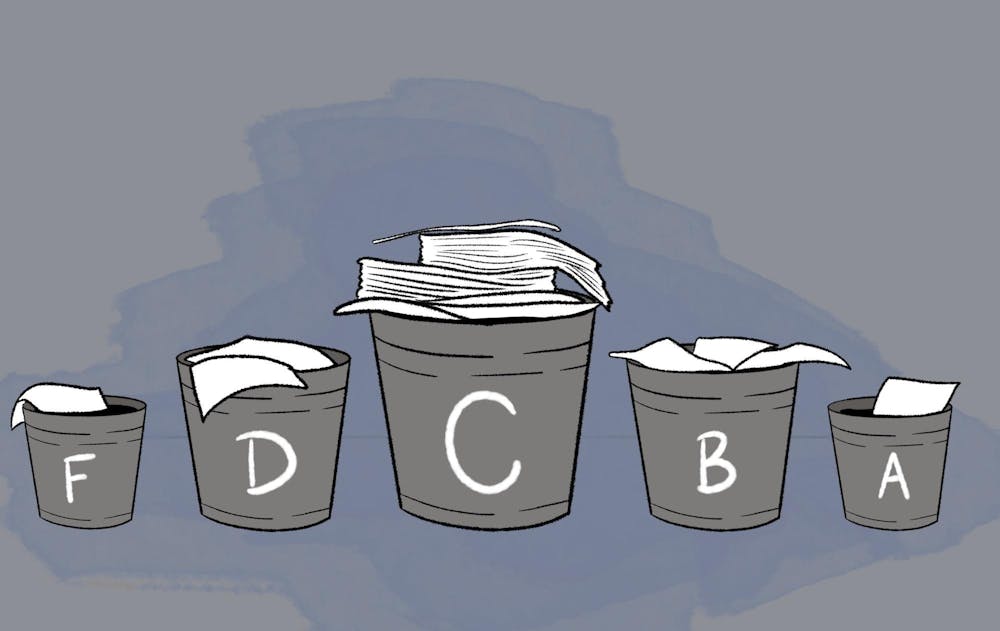

And so, to make their classes fit into the rigid curve requirement, professors must resort to creating harder, even obscure exams in order to have grades reflect a bell curve — or take the more harrowing option of curving students down a letter grade at the end of the semester. In either case, students’ grades do not reflect mastery of the subject material. A universally imposed curve means that curving a student's grade upward creates a false impression of greater mastery, while curving it downward implies less mastery than the grade suggests. The need to display or fit into a perfect normal distribution, then, is framed as more important than measuring students’ proficiency. When a classroom has a curve, one idea reigns supreme for grading — that meaningful academic success or rigor for one student necessarily comes at the expense of another student’s guaranteed mediocrity or failure.

Unless Batten wishes to preach a dangerous philosophy of a zero-sum world, where one employee gets promoted at the expense of another, the school must do away with its curve. The very idea of simulating a cutthroat environment is at odds with fostering a supportive school community, and we should not mix up the two in the classroom. After all, collaborative work — the very style of learning that Batten is centered on — is a life skill necessary for long-term success in the workplace. This is not to say that the world of employment does not also demand the sort of competition intrinsic in the curve. But college is not supposed to be a workplace. Removing the curve gives Batten a chance to truly promote the values of collaborative learning.

The Batten School must allow professors to design grading systems tailored to the needs of their own students. Top-down enforcement of flawed grading policies has squashed classroom collaboration and placed professors in impossible situations. Luckily for the Batten School, this is one of the few policy issues in the world that has a truly straightforward solution — just remove the curve.

The Cavalier Daily Editorial Board is composed of the Executive Editor, the Editor-in-Chief, the two Opinion Editors, the two Senior Associates and an Opinion Columnist. The board can be reached at eb@cavalierdaily.com.