For Gary Ham, the University’s first Black football player on the varsity team and Class of 1973 alumnus, the key to being a Black student at a majority-white university was simple — resolve and resilience.

“Growing up, I’d run the whole gamut of racism and prejudice in my young life … It still hurts,” Ham said. “You just developed a resolve to continue to stand, to accomplish, and I think that’s probably one of the great legacies of some of the great leaders in African-American communities faced with overwhelming challenges to even go forward. They did it.”

Before his time at the University, Ham grew up in a military family — his father was one of the few African American men in the Air Force.

In 1969, Ham came to the University on a scholarship — but not for football. It was an ROTC scholarship, and he did not plan to play football in college. He was there to pursue a degree in sociology, which he earned upon his graduation in 1973. In his first year, he watched the team play en route to a 3-7 record and decided to try out for a varsity football program that had never fielded a Black player.

“I played football in high school, and I loved the game,” Ham said. “Of course, that was nowhere near what college football was like. My love for football was there, and therefore I went out for football when I got to U.Va.”

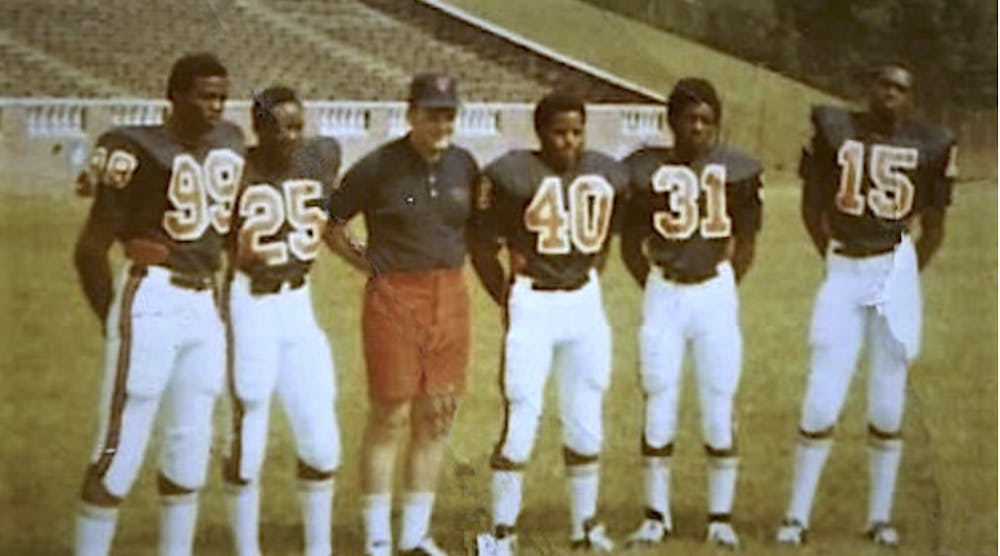

Ham tried out for the team in the spring and was invited to join the varsity team as a walk-on cornerback. The four Virginia Black players — Harrison Davis, Stanley Land, Kent Merritt and John Rainey — all played for the freshman team at the time, making Ham the first Black varsity football player at Virginia.

Ham’s football career ended prematurely due to an injury prior to his senior season, but he still had some signature moments as a Cavalier. One came in 1972, when Virginia played host to West Virginia. That season, Mountaineer junior wide receiver Danny Buggs averaged a touchdown every five times he touched the ball — he was an All-American and future NFL wideout. Ham, who was on special teams, remembers tackling Danny Buggs — although he admits that describing it as a tackle may be a generous characterization.

“It was really quite a moment because I didn’t start or anything like that,” Ham said. “I remember getting hit by this real big guy, he hit me and I went down, but I popped back up. As soon as I popped up, I realized the runner, the guy who caught the ball, was Danny Buggs … and I hit his foot or something and tripped him up. That was my claim to fame.”

Aside from taking down an All-American, Ham contributed to Virginia athletics in other ways. Following his injury, he joined the track & field team in the spring of 1973 in an effort to stay involved.

“I just felt that I never really achieved my goals for football,” Ham said. “My football time was over … February of ‘73 — that was my senior year — I wanted to do something else with sports.”

Integration at Virginia was a painstakingly slow process, opposed at every step. The first Black student — admitted into the Law School — arrived on Grounds in 1950, but students bitterly resisted integration through the 1950s and into the 1960s. This pattern remained consistent in Virginia Athletics — the Virginia program was the last ACC program to integrate upon Ham’s acceptance onto the varsity team.

For Ham, the football experience was a mostly positive one despite the racial disparity. However, his experience at the University at large was marked less by acceptance and more by prejudice. Just as the country was experiencing a racial reckoning, so was the University, and Ham vividly recalls a manifestation of that reckoning.

In the spring of 1970, Ham’s second semester on Grounds, students began protesting against the war in Vietnam and the low level of African-American enrollment, among other issues. These events came to be known as the May Days of 1970 — in Ham’s eyes, they were a result of University integration lacking buy-in from the larger population.

“I was at the Lawn when the state troopers drove right down the Lawn with those long, big trailer trucks,” Ham said. “Those troopers got out of those trucks, and they went onto the Lawn and they started arresting [people]. Black kids, when we saw that, we said, ‘We’re not getting anywhere near that.’ Because we said, ‘If they treat white kids this way, what will they do to us?’”

In the wake of these events and early in his time at the University., the most critical moment for Ham came not with the football team, but with a guest speaker on Grounds, a Black minister named Tom Skinner — who came as a part of Black History Month in 1973. Ham recalls being deeply affected by Skinner’s message.

“His life was our lives,” Ham said. “His struggles were our struggles. If you really want to find respect … begin with getting a relationship with Jesus Christ.”

Ham’s experience with religion at the University was one shared by many of his peers. Ham spent much of his time with the around 20 other African American students at an African American church that gave them meals and a sense of community. Religion, Ham says, defined an entire generation of African American students struggling with the oppression of their time.

“[African American leaders] were shouting to our culture, to our society, ‘Recognize me, respect me, affirm me regardless of the color of my skin,’” Ham said. “No matter what color you are, you’re born with this innate desire to be valued and to feel respected. That’s the God-given thing. The better way of finding that is a relationship with Jesus Christ.”

After graduating and fulfilling his four-year military commitment, Ham attended Elim Bible Institute in Lima, N.Y. He then graduated in 1980 and pursued a career in gospel ministry — he is still involved in ministry in upstate New York.

Looking back, Ham is proud of how the University has grown more accepting — Ham notes how “encouraging and promising to see such community and diversity at U.Va.”

He may no longer reside in Charlottesville anymore, but Virginia is never far from his mind. When Virginia heads up to play Syracuse, he makes sure to watch — and, of course, he keeps a close eye on the football team.

“I’m an avid fan,” Ham said. “Wahoo all the way.”