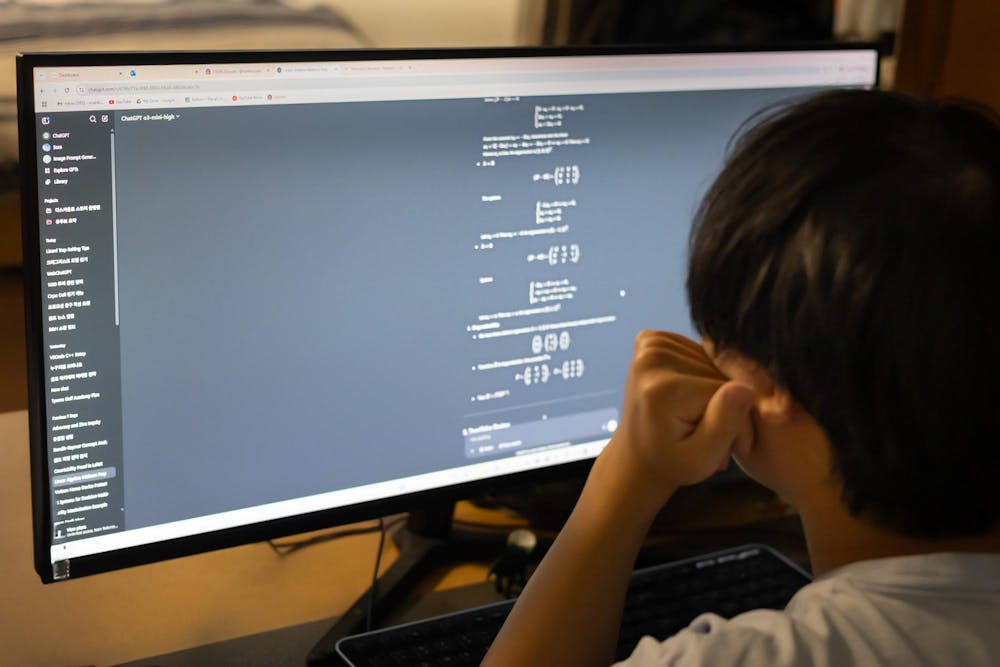

Generative artificial intelligence, such as ChatGPT or Microsoft Copilot, has become widely used in classes as a learning tool and homework assistant. Although the University provides guidance on the use of generative AI, there is no universal policy which addresses the extent to which it may be used in classrooms. As a result, faculty have been granted a fair amount of freedom to choose how generative AI may be used in their classes, but some students say they have been largely left out of the discussion.

Since the University conducted a task force report on generative AI in teaching and learning in the Spring 2023 semester, the University Office of the Executive Vice President and Provost has provided faculty and students with recommendations on how generative AI may be used in and outside of the classroom. The website advises professors and students on the risks of generative AI, including privacy concerns, and notes that professors may not use generative AI to grade assignments, or use a generative AI checker on assignments, due to their inaccuracy.

Despite this, the website repeatedly states that professors may be able to choose how and when generative AI is used in their classes, and offers several recommendations on how to do so, such as informing students about how to use generative AI as a study tool which can explain confusing topics.

Ryan Nelson, the Murray Family Eminent Professor of Commerce Director, said that there are many instances in which generative AI is not useful for developing critical thinking skills, and many cases where students can use it as a tool.

“There are a number of faculty that will just not allow the usage of generative AI in almost any shape or form, because they really want to develop critical thinking in their students,” Nelson said. “And then the other end of the continuum is our faculty that wants to make sure that students are well prepared to enter the workforce using artificial intelligence as effectively as possible.”

Assistant Professor of Commerce Reza Mousavi noted the inevitability of generative AI use in the workforce is a common reason as to why professors, especially at the McIntire School of Commerce, are promoting the use of generative AI as a tool for research, planning or editing for assignments.

“When [students] join the workforce, in many, many cases, [employees] are allowed to use ChatGPT … and most of the companies right now have their own AI tools,” Mousavi said. “So because of that, they should be able to use and leverage these tools to enhance their performance, save time, and be more efficient. But don't take shortcuts.”

The distinction between generative AI as a learning tool and generative AI as a shortcut varies from one professor to another, but many shared thoughts about how it can be used in ways that support learning without undermining critical thinking. Spyridon Simotas, assistant professor at the college, allows and encourages the use of generative AI in his language learning classes as a means to enable a better understanding of French, without relying on direct translation.

“The difference between AI and other technologies in the past like Google Translate is that you can ask questions,” Simotas said. “With AI you can tell it to work with you at your level. And this is what I find fascinating, because you can stay in the language and create conditions as a learner to keep you in the language without having to default into translation.”

Simotas and other professors have created their own policies following recommendations from the University’s task force, which engaged with around 300 faculty across six town halls in gathering information for its report and gathered survey responses from 504 students and 181 faculty. Although professors have a large amount of control over their generative AI policies, some students continue to feel that they do not have the opportunity to share input on these policies.

Second-year College student Ella Duus is currently researching student self-governance of generative AI at the University, through a literature review on the history of student participation in self-governance, as well as student governance surrounding data and information technology. She noted the lack of student input on the topic of AI policies in classrooms.

“There has not been formal student input, especially not at the same level that was offered to faculty,” Duus said. “And although faculty have a very important voice to offer because … they're the ones teaching, students are the ones learning. I think it would make sense for the University to invest some time and effort in collecting formalized student feedback on this and then moving in the direction, if feasible, that students want.”

Some students have concerns surrounding the future of generative AI and education. First-year Engineering student Sara Mansfield noted that she believes generative AI should not be used in place of human thinking. However, she disagrees that students necessarily need to have more input on generative AI policy.

“I know that student self-governance is a huge thing [at the University], so student input would definitely be helpful,” Mansfield said. “But at the end of the day, I think the professor knows best what the professor is teaching in the class and how much AI can either help or hinder learning that material.”

Assistant Professor of Commerce Kiera Allison, in an effort to include students in the policy-making process, explained that in her class this semester, she chose to have students vote on which generative AI policy they prefer. She explained the purpose behind her policy is because she believes policies work better with social consensus behind them and wants students to form an opinion on generative AI policies in her class.

Ultimately, her students chose a policy which allows them to use AI to generate or revise up to 20 percent of their work, without having to report that they had used it.

“If students have had to articulate among themselves why this policy works for them and why they think this should be the code … then they've had to persuade themselves already that this is the policy they want to adopt,” Allison said. “Whatever policy I impose doesn't just affect that student, it affects the other students around them.”

Not every professor, however, views generative AI as a positive development for learning — although despite this, they still find ways to educate students on how to use the application responsibly. John Owen, Taylor Professor of Politics at the College, asks students to compare their own written work to that of generative AI. Following an in-class essay written by students, Owen asks them to put the same prompt into any generative AI platform and discuss where the generated essay falls short in comparison to their own writing. Besides this, he generally does not authorize the use of generative AI on assignments.

“In absolute terms I regard it as a negative development,” Owen said. “...I believe that early assembling of work is essential to the writing task and also to thinking, including thinking on one’s feet when in an oral discussion. So from a teaching standpoint, I think we would be better off without AI.”

Mousavi also emphasized how important it is for the student to still be doing the thinking behind their assignments.

“If you just use it to take shortcuts, it is going to kill critical thinking,” Mousavi said. “So it's a double-edged sword. It's a tool. If you use it properly, it is going to definitely help you. If you use it improperly, it is going to hurt you.”

Professors also discussed how noticeable the use of generative AI on assignments has become. They noted the new standard of perfection on assignments, and the abundance of perfect scores that, before the widespread use of generative AI, were few and far between. Allison explained the higher level of writing perfection that she has come across on assignments. She said that this has made her focus less on writing quality and more on other parts of assignments.

“There's a level of cosmetic perfection that more students have access to,” Allison said. “Honestly, my response to that is [that] I'm less interested in perfect writing. I want something that looks like a human worked through it, right? So I'm looking for a kind of unique cognitive imprint.”

Simotas also noticed a shift in assignment grades since the use of generative AI. He explained that the general standard of assignment submissions has increased since generative AI has become accessible. He highlighted that with the rise of generative AI use, improved grades do not always indicate that students are learning material more thoroughly.

“I don't think that a perfect score necessarily meant better learning,” Simotas said.