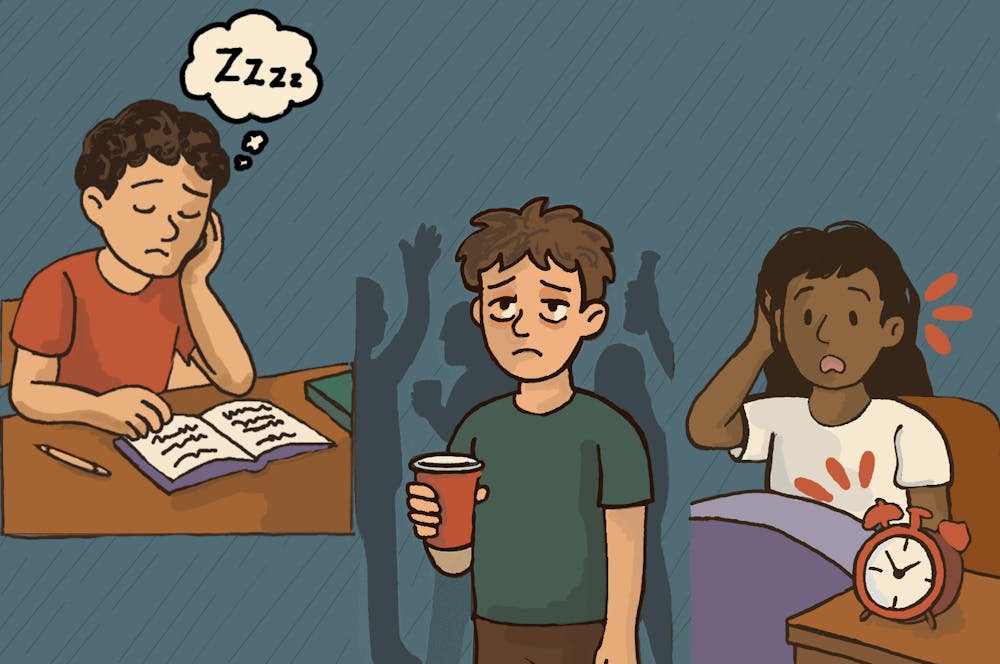

From cramming for tests until dawn to waking up for early morning workouts, more than 60 percent of American college students experience poor sleep. In the wake of academic, extracurricular and social demands, getting the recommended 7-9 hours of slumber is essential — but it is often the first part of a healthy routine that students cast aside.

This is no different at the University. Despite the fact that sleep is a key component of good mental and physical health, many students across schools at the University feel they cannot prioritize sleep above their to-do list. These students say that sacrificing sleep has become an unavoidable part of their life at the University, and although they have found ways to adapt, they express concern that a sleepless study body is being normalized.

According to graduate College student Andi Wood, the culture of sleep deprivation at the University stems from the pressure of prestigious academics. She said that each professor expects a high level of performance, seemingly dismissing that most students take five or more similarly time-consuming courses.

“In undergrad, especially from the top, they expect you to get your work done and don’t care how much sleep you’re getting,” Wood said.

This trickles down to the students, Wood said, who struggle to meet those expectations and shape their sleep habits accordingly. As a result, she said, sleep deprivation becomes a normal part of student life and almost a badge of honor.

“At the bottom, it’s kind of like the no sleep Olympics,” Wood said. “There is a big culture [of] not sleeping, and that’s the norm. That definitely should not be the case.”

Second-year Architecture student Hailey Hicks said she finds herself falling victim to the culture of sleep deprivation and her circadian rhythm disrupted by a demanding workload. In the School of Architecture, she and her peers frequently complete extensive, hands-on projects for their classes, and to perfect their models, it is not uncommon for them to work from sunset to sunrise.

“I normally go to bed around 1 or 2 [a.m.],” Hicks said. “And then on weeks where we do have a project deadline, I [go] to bed anywhere between 3 to 4 [a.m.] most nights. Two nights ago, I went to bed at 6 a.m., which is pretty common.”

Second-year College student Jessica Yi said that she understands the importance of sleep to her well-being. Yet, no matter how much she wants to get these solid hours, she finds that they just do not fit into her schedule. As a biology student taking courses in organic chemistry and genetics, she constantly finds herself studying for exams late into the night at the library.

“I’ve been thinking, ‘Sleeping late is so bad for my body,’ and my mom always tells me it messes up your hormones … but I can't get myself to sleep early, I just can't,” Yi said.

Hicks agreed with Yi, saying her work often takes priority over sleep, which comes at the detriment of a proper routine.

“[Sleep] is definitely a secondary thing,” Hicks said. “The word ‘schedule’ is arbitrary to me — it’s more so [that] everything’s out the window. I get as much sleep as I can, but work comes first at times.”

Academic demands are not the only thing that keeps students from getting to bed. Beyond maintaining a high GPA, University students feel pressure to build glowing resumes and lead a well-rounded lifestyle. Students, on top of their rigorous coursework, bounce between club meetings, on-Grounds jobs and volunteer shifts.

Second-year Commerce student Odessa Zhang says that the expectation to be active in clubs and hold leadership positions shaves away at her sleep. She said that these commitments often have her saying no to social invitations, too, as she needs to opt for rest over a night out.

“A lot of my extracurriculars tend to meet later at night. Same with group projects,” Zhang said. “In addition to that, when I have things in the morning [like] my morning internship, I have to wake up early for calls, which can make me lose sleep.”

Students admit that procrastination — whether it be in the form of watching Netflix or going to a house party — may occasionally contribute to sleep deprivation. But according to Hicks, while procrastination seems to be a common explanation for students’ lack of sleep, it is not always a significant factor. She said that the pressure to accomplish everything, and to do it well, simply does not allow students to get the sleep they need.

“Genuinely, I feel like a lot of people think that it’s just [that] we procrastinate, [but we’re] actually not,” Hicks said. “It’s just we have so much work and it all piles up at one point in time … and have other things going on, like all the students at U.Va. … and that’s why we work into the night.”

To cope with poor sleep, many students employ timeless strategies of downing caffeine and returning home for a siesta. Third-year Engineering student Zack Sikkink does just this, compensating for missed sleep with coffee and midday naps. With the difficulty of upper-level engineering courses, he said that caffeine is especially necessary to focus and work productively in a sleepy haze.

“I drink at least one cup of coffee per day, sometimes up to three,” Sikkink said. “If I’m sleepy during the day, I’ll take a nap.”

Zhang also said that coffee has become a dependable part of her everyday routine.

“I do drink coffee every single morning,” Zhang said. “I need caffeine in the morning, otherwise I'll probably be tired for the rest of the day.”

Although students find ways to adapt to the stress of little sleep, the normalization of sleep deprivation at the University has stirred concern among students across major programs and schools. Speaking from her experience as an architecture student, Hicks said that she thinks there needs to be a fundamental shift in the way students and faculty reckon with sleep.

“I think it's a change in culture that needs to [happen],” Hicks said. “I don't think that it should be common for me to be in the A-school and at night there's twenty of us in there [at] 4 a.m.”

But, evidently, the issue of sleep runs deep in every aspect of student life, not just academics. According to Wood, the sheer number of things to do and places to be becomes borderline unhealthy for students, and things need to change.

“At a big academic school like U.Va., there is so much to be done, and that does hurt students,” Wood said.